Sustaining Students’ Increased Achievement Through Second Order Change: Do Collaboration And Leadership Count?

"In an increasingly competitive, financially constrained and uncertain world, schools and school districts are undergoing major changes. In this environment, teachers and leaders need both individual and collective assistance to acquire the capacities for adapting to these changes (Sharratt, 1996, p.1)".

In the last decade, in many countries and jurisdictions, school systems have devoted much attention to the issue of developing staff and leadership capacity. Contextual and cultural differences abound but building staff capacity has made a difference in the school district we represent as well as in the Province of Ontario generally. Just as important is the sustainability of improvement efforts that will, no doubt, be the subject of much continued debate and research.

In this paper we delve into the issue of sustainability of student achievement by examining and reflecting upon actions taken by a large school district with which we are associated. It is a particularly appropriate case for the topic, because the district has been intensively engaged in district-wide reform for the past five years and has relied heavily on mobilizing leadership and collective effort, at all levels of the system, to increase students' literacy achievement. More recently, in order to go deeper and sustain its student improvement efforts, the district has realigned its processes and structures to further sharpen the focus on its core literacy priority with the intent of raising the bar and closing the gap for all students. It is this process that is being referred to as 'second order change'.

The questions of interest for the purposes of this paper are threefold. First, 'what specific elements propel a large system from first order change towards second order changes thereby sustaining improvement processes? Second, 'What does this district need to do to ensure sustainability of students' increased literacy achievement?" and third, "do collaborative processes and distributed leadership practice have a positive impact?'

We first provide some context in describing the district planning process and the Literacy Collaborative (LC) model that has been the focus of reform. Second, we present pertinent literature on the complexity of systemic change and the importance of organizational and school culture and as well, we examine the literature on collaboration and leadership processes. Third, we address the substance of sustainability and second order change by drawing directly on our data. Finally we conclude with the recommendations for sustaining achievement, considering elements that appear to be important underpinnings for transition from first order to second order change processes.

1. DISTRICT CONTEXT

The York Region District School Board (YRDSB) is a large diverse district just north of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is rapidly growing with a varied socio-cultural and linguistic population with over 100 different languages spoken in the schools. On average, the school board has been opening 5 new elementary schools a year for the last five years and a secondary school every other year. There are now a total of 151 elementary schools and 30 secondary schools comprising a school system with over 115,000 students and 8,000 teachers.

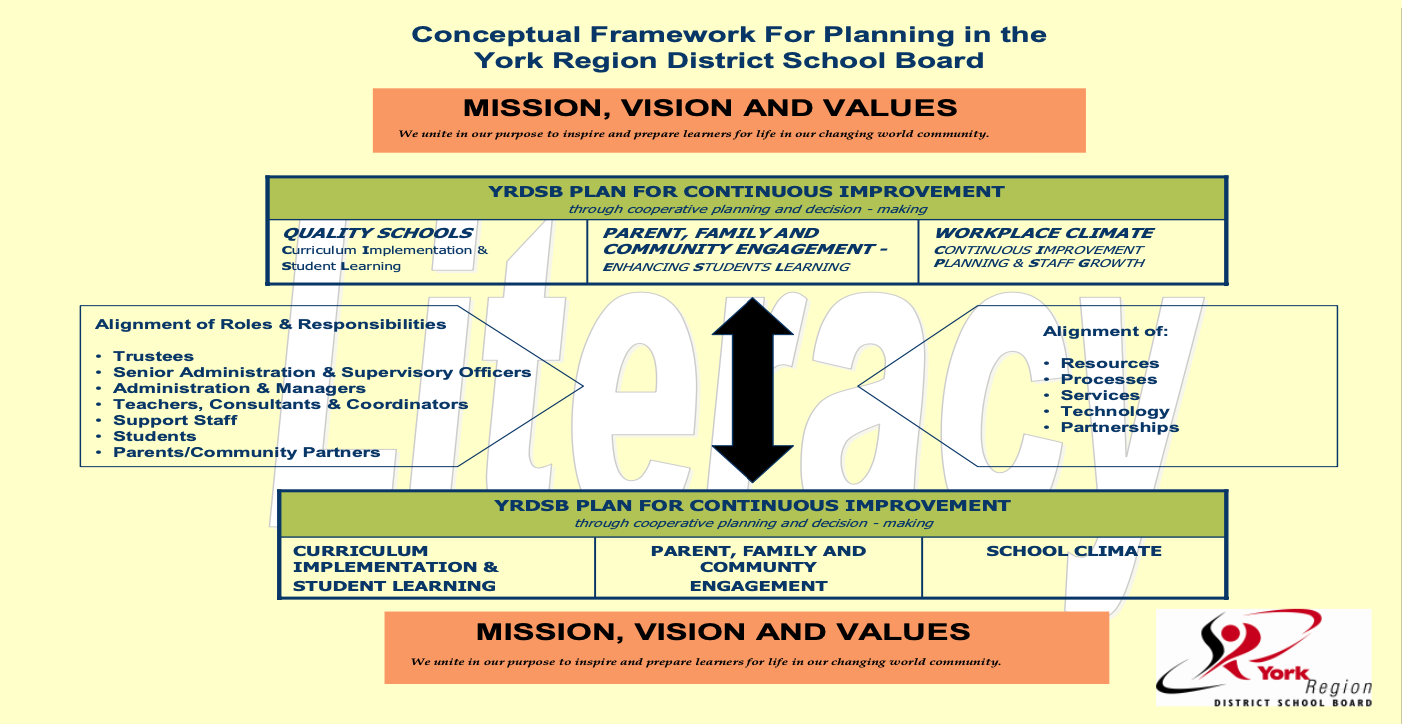

In 2000 when the district began its student achievement improvement strategy in earnest, the Director of Education, (equivalent to the Superintendent in the United States), set out to develop the best possible model for reform drawing heavily on external ideas but developing a capacity from within the district to lead the reform with a critical mass of leaders at all levels of the district. With recognition of the direction that was required, the system went through a process to develop its mission statement and the implementation of a common and consistent school planning process to consolidate the literacy focus that comprised the core priority in the district's Plan for Continuous Improvement. Consistency was brought across the system by an emphasis on the need for alignment and coherence of district and school-based initiatives. This alignment is reflected in Figure 1 below and demonstrates a key focus of the system through the early period of the system's planning efforts to improve student achievement.

This framework, embedded in the core values of the organization and developed for use with schools by superintendents, demonstrates the three core areas of the Board Plan for Continuous Improvement and their alignment with the same three core areas of the School Plan for Continuous Improvement. Literacy is the watermark behind this graphic symbolizing the intentional focus and centrality of our Literacy priority.

The district addressed its literacy focus through a model that came to be known as the Literacy Collaborative (LC). Key features of the approach included:

-

Articulating a clear vision and commitment to a system literacy priority for all students and continually communicated to everyone in the system;

-

Developing a system-wide comprehensive plan and framework for School Planning for Continuous Improvement (SPCI);

-

Using data to drive instruction and determine resources;

-

Building administrator and teacher capacity to teach literacy for all students; and,

-

Establishing professional learning communities at all levels of the system and beyond the district.

The district developed a strong team of Curriculum Coordinators and Consultants, all focused on facilitating balanced literacy instruction. It also linked into external research development expertise, particularly with the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE/UT). Assessment of the effectiveness of the implementation was evaluated annually. Capacity building focused on literacy assessment for learning, instructional strategies, and on change management. In this case, capacity building means any strategy that develops the collective efficacy of a group to raise the bar and close the gap of student achievement through 1) new knowledge competencies and skills, 2) enhanced resources, and 3) greater motivation. The operative word is collective - what the group can do, whether it is a given school or indeed the whole district, to raise the bar and close the gap of student achievement (Sharratt and Fullan, 2005, p.2).

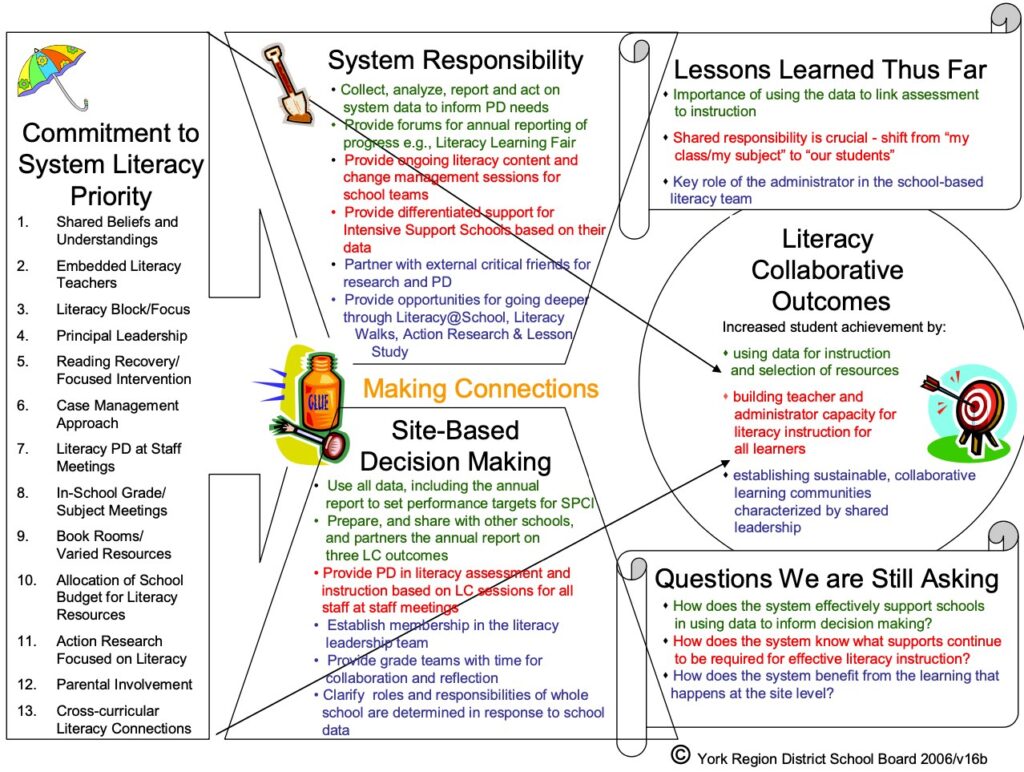

The district has invested in on-going, systematic professional development in literacy, assessment literacy, knowledge of the learner, instructional intelligence, and e-learning, as well as professional learning focusing on change knowledge (understanding the change process, dealing with resistance, building professional learning communities, leadership and facilitation skills, and the like). The complete model is shown in Figure 2 below.

The model may appear overwhelming and we do not intend to explain it in detail here. In fact, the model was developed over time and is presented and discussed on an ongoing basis within the system to clarify the overall vision and to continuously improve the approach. Our point here is that the model is explicit, evolutionary (open to refinement based on ongoing evidence) and comprehensive. It reflects and guides the work of the district and is used by instructional leaders at all levels of the system and we define the work, thus far, as first order change.

Table 1 shows overall results of the Provincial Educational Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) assessment administered to all Grades 3 and 6 students in Reading, Writing and Mathematics over time. As well, it shows our growth in ESL/EDL instruction in the same population, our results in the Grade 10 Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test (a diploma bearing assessment), and our improvement in students' reading by the end of grade one. While the data show impressive overall results and increased student performance over time, we have questions about sustainability and also the improved results of various sub groups found within our general population as we look more closely at the data.

Table 1: 6-Year Span in EQAO Results in YRDSB (1999-2006)

| EQAO (Method 2) | 1999 (baseline year before District Literacy focus) | 2006 | % Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participating Students | |||

| Grade 3 Reading | 59 | 74 | 15% |

| Grade 3 Writing | 66 | 78 | 12% |

| Grade 3 Mathematics | 70 | 81 | 11% |

| Grade 6 Reading | 61 | 75 | 14% |

| Grade 6 Writing | 59 | 75 | 16% |

| Grade 6 Mathematics | 63 | 76 | 13% |

| ESL/ELD Learners

% ESL/ELD Learners |

Gr. 3 4%

Gr. 6 4% |

9%

7% |

5%

3% |

| Grade 3 Reading | 34 | 66 | 32% |

| Grade 3 Writing | 47 | 75 | 28% |

| Grade 3 Mathematics | 62 | 77 | 15% |

| Grade 6 Reading | 27 | 67 | 40% |

| Grade 6 Writing | 27 | 74 | 47% |

| Grade 6 Mathematics | 62 | 79 | 17% |

| OSSLT (Grade 10: 15 year olds: diploma bearing assessment) | Oct 2002 77% | Mar 2006 88% | 11% |

| Reading at the end of Grade 1 (PM Benchmark Assessment Tool) | 59% | 84% | 25% |

First order change is clearly in place as evidenced by our overall achievement; however, we wonder if sustainability is possible and what would ensure that the improvement noted is embedded in sound assessment and instructional practice in all 8800 teachers' classrooms in YRDSB (second order change). Thus, for the purposes of this paper our research questions are:

- What specific elements of first order change propel a large system from first order change towards second order changes which sustain improvement processes?

- What does this district need to do to ensure sustainability of students' increased literacy achievement?

- Do collaborative processes and distributed leadership practices have a positive impact? These questions first lead us to examine the research literature on change, culture, organizational learning that leads to establishing professional learning communities, capacity building that leads to collaboration, leadership that drives it all, and finally what the literature says about the complexities of moving from first to second order change, the central investigation of this research paper.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Change

Change and restructuring involve reculturing, unlearning and relearning (Hedberg, 1981, p. 18) and fundamental alterations in relationships (Prestine, 1994, p. 1) within organizations. This will be difficult, as Huberman argues (in Prestine, 1994, p. 31), because schooling is a "complex, coherent, and resilient ecosystem . . . with an awesome capacity to wait out and wear out reformers." The enormity and difficulty of the task is just now becoming clear for schools involved in restructuring. Louis and Miles (1991, p. 86) concluded, for example, that "programs that reach into the classroom, and those that require more change in the current assumption about what constitutes `real school' - are likely to increase the rate of problems encountered." "Change in teaching requires major transformation in the culture of a school, a complex undertaking" Fullan warns (1993, p. 54). As well, Prestine (1993, p. 21) adds that school-wide governance and organizational changes (first order changes) are easier to make than changes in curriculum and pedagogy in classrooms (second order changes). Those areas will require the active engagement, participation, and commitment of nearly all members of the organization in order for such efforts to succeed.

Environments that support a balance between organizations' abilities to learn and unlearn appear necessary for long-term survival. Unlearning ability is needed in order to make room for more adequate interpretive frameworks and responses in organizational memory (Hedberg, 1981, p. 19- 20). Hedberg notes that organizations learn when they interact with their environments, but their environments are largely artifacts of the mental maps of the organization. Frequently, large organizations allocate their resources to manipulate and change their environments rather than reflect on and change the real reason for their problems: their own behaviour (Sharratt, 1996, p.21). Similarly, at the school level, when a teacher changes practice from a lecture format to co- operative learning in her classroom, she changes the relationship patterns, rules and underlying assumptions of her practice. As new changes become internalized and continue to grow, change needs to be embraced as an ongoing process of consideration of culture at both system and school levels.

Schein (1984) suggests that to really understand a culture, it is important to delve into the underlying assumptions, which are unconscious but which actually determine how group members perceive, think, and feel. Cultural assumptions can be thought of as a set of filters or lenses that help us focus on and shape our perceptions of the relevant portions of our environment; otherwise, we experience overload and uncertainty. These taken-for-granted, tacit, and often un-discussable assumptions, as well as norms, values, and mental models, are mentioned frequently in the literature as being very powerful and the most necessary to change, if organizational learning is to occur. It would appear that it is easy to make changes that are in line with present assumptions, and very difficult to make changes that are not (Schein, 1984, p. 14). Thus, we next consider culture as the ostensible normative glue of an organization can be both a source of strength and restraint.

2. Culture

The framework for Sharratt's study (1996) argued for the central importance of organizational culture in sustaining long-term organizational learning. Organizational culture influences all of the other factors and conditions which indirectly and directly affect the organization's ability to learn, unlearn, relearn and retain new practices (Hedburg, 1981, p. 6).

One positive way to deal with cultural conflict is to be aware of the differences between discussion and dialogue. The purpose of dialogue is to go beyond any one individual's understanding. A group explores complex, difficult issues from many points of view. In a discussion, different views are presented and defended. There is a winner and a loser. Both dialogue and discussions can lead to new courses of action, but actions are often the focus of discussion, whereas new actions emerge as a by-product of dialogue (Senge, 1990, p. 247). Dialogue is a team activity, needing reflection and inquiry. Conflict is productive to teams. The free flow of conflicting ideas is critical for creative thinking, for discovering new solutions no one individual would have come to on his/her own. Thus, conflict becomes part of the ongoing dialogue (Senge, 1990, p. 249).

However, the real work of school improvement and cultural reform takes place inside individual classrooms. Teachers need a culture and a structure within which to build trust, and to cut through the "dailiness" of their work lives (Leiberman, 1988, p. 150-151). Nias et al. (in Fullan, 1993) conclude that major change is inherently and persistently complex, and that individual and shared concerns must coexist in dynamic tension. As one teacher summed it up, "life isn't really about being alike and sharing the same attitudes. Tension is part of collaborative working" (Nias, in Fullan, 1993). Of importance, as Bryk and Schneider (2002) suggested, in highly effective schools, trust becomes a substantive property of the social organization. Schools in which trust levels are high are able to examine professional practice in more critical manner integrating conflict and collaboration in constructive ways. New teachers being integrated into an existing culture of collaborative or isolationist practice will experience the culture's inductive power of 'the way things are done around here'. Yet as Schein offered, "the very process of passing on the culture provides an opportunity for testing, ratifying and reaffirming it" (1984, p. 14). When visions, values and beliefs are widely shared, it is believed that the culture may be steered through an organizational course in an agreed upon direction (Sergiovanni, 2000). When a culture is steeped in conflicting values, it appears that conflict, sensibly enough, is the general outcome (Achinstein, 2002; Lipman, 1997). Reculturing appears to demand a new lens to be developed through which to view and experience the organization. As Fullan (1996) highlighted:

The nature of the reculturing we are talking about is developing collaborative work cultures that focus in a sustained way on the continuous preparation and professional development of teachers in relation to creating and assessing learning conditions for all students...it is truly a massive change because it goes to the core of the culture of the schools, and must eventually go hand in hand with major structural changes (p. 220).

3. Learning Organizations that Lead to Professional Learning Communities

How do we distinguish a learning organization from a learning community? While a learning organization such as a school system must be concerned with outcomes, accountability and efficiencies, a learning community is concerned with the growth of all its members. It sees leadership as being broad-based participatory and distributed. As Sergiovanni points out, "who controls what and how has direct consequences for the kind of profession teaching will become" (2000, p. 77). School capacity for organizational learning appears to be contingent upon what Marks and Seashore Louis call "constituent dimensions" which include structure, shared commitment, collaborative activity, knowledge and skills, leadership, and feedback and accountability (1999, p.712). Their analyses also found a consistent relationship between the capacity for organizational learning and teacher empowerment. Certainly, in the experience of the York Region District School Board, teacher empowerment through capacity building continues to be a mainstay of improvement efforts and professional learning experiences. The concept of teaching as a learning profession is increasingly relevant to the debate of how to sustain improvement and continue to build capacity. As Emihovich and Battaglia (2000) contend, it is the role of those in leadership to develop a collaborative culture of inquiry. Leaders who become participants in collective inquiry appear better able to provide scaffolds of support within their school cultures. Reflective inquiry also demands critical assessment of our own effectiveness as educators. Swieringa and Wierdsma (1992) remind us that in a learning community individual and collective learning are deeply embedded in each other and contradictions and conflict are a part of the process.

Researching what they call the "paradox of professional community" within two high schools, Scribner et al. (2002) reported that attention to individual needs and professional autonomy were necessary and important conditions of professional communities. A delicate balancing act is necessary to attend to individual and organizational needs and development. The principal is seen as an indispensable arbiter of the tensions between levels of needs - individual and organizational.

4. Capacity Building that Leads to Collaboration

Let us consider the frequently used term 'capacity building'. We use it in framing work in schools that is increasingly deprivatized and collaborative. It has been suggested that systemic goals regarding capacity building include creating the conditions, opportunities and experiences for collaboration and mutual learning (Harris, 2001.p. 261). As Lambert has suggested, this perspective embraces the notion of a professional learning community in which teachers may participate in decision making, have a shared sense of purpose, engage in collaborative work and accept joint responsibility for the outcomes of their work (1998). Empowerment and inclusion are the underpinnings of this view of collaborative capacity building and these elements are integrated in the York Region District School Board's Literacy Collaborative conceptual framework (Figure 2) for systemic improvement. Building capacity is thus a dynamic process and one that is highly complex. Rather than a focus on capacity building being simply a school imperative, Mitchell and Sackney (2000) would suggest that three critical capacities need to be developed simultaneously - personal capacity, interpersonal capacity and organizational capacity. Our school district has taken pains to develop these three capacities that foster growth both as a learning organization and as a system inherent with many different learning communities.

Much of school reform appears to rest on the shoulders of the broadly accepted but ambiguous term 'collaboration'. Individuals tend to experience 'collaboration' in many forms in the day-to- day operation of classrooms and schools. The structure in which collaborative work takes place may be labeled in many ways - school leadership teams, committees, grade partnering, learning teams, study groups, action research collectives - to name a few. It is the nature of the work that is at the heart of the matter. It involves working with colleagues and often involves a degree of intentionality that deepens the interaction. Viewed broadly, the following definition is useful beginning point:

Professional collaboration is evidenced when teachers and administrators work together, share their knowledge, contribute ideas, and develop

plans for the purpose of achieving educational and organizational goals. (adapted from Cavanagh & Dellar as cited in Leonard & Leonard, 2001, p.7)

Fullan suggests that contemporary school improvement processes need to be fueled by highly effective collaborators in order to change practice and improve student achievement (2005). We would contend that the notion of effective collaboration involves the participation of collaborators who are specifically influential with colleagues - the collaborator as a critical change agent, so to speak. However, as research recently highlighted (Planche, 2004; Planche, 2007) while principals and teachers articulate good intentions about working together in dynamic and effective ways, their work also appears significantly complicated by the complexities of interpersonal relationships and the impact of working cultures. As well, trust appears a prerequisite to developing deeper forms of collaborative work. Indeed, as Hardin offers, trust is both a result and a precondition of co-operation (2002, p.84). For example, the shared analysis of student work and the shared analysis of instructional effectiveness require the firm grounding of trusting relationships among educators (Langer, Colton & Goff, 2003). Underneath issues of trust remain long-standing issues of compliance versus commitment. Collaborators within schools are also employees and part of well-defined structures within institutional life. In the case of school systems, the work structures within the system shape and limit the opportunity for deeper forms of communication and discourse. Thus, the degree of relational trust that develops between colleagues becomes an important factor in coping with the limitations imposed by the institution itself. While the term collaboration is used loosely and widely to name a wide variety of interactions amongst school professionals, the substance of collaboration runs the gamut of reflecting weak to strong ties of professional engagement (Little 1990).

References to collaboration are made frequently in the literature as an element of reculturing schools (e.g. Cocklin & Davis, 1996; Fullan, 1996; Hargreaves, 1995). Hargreaves (1996) viewed teacher cultures as the patterns of relationships and forms of associations between members of the culture and identifies four broad types: (1) fragmented individualism, (2) balkanization, (3) collaborative culture (including bounded collaboration), and (4) contrived collegiality. Cultures of collaboration, Hargreaves argued, are central to the daily work of teachers (1996, p. 273) and, we add also central to the daily work of system and school leaders.

5. Leadership that Drives it All

The principal as an influential and key collaborator is evident in much of today's literature on leadership. We know from the research that the leadership role of administrators in the school impacts student improvement in a small but educationally significant way. (Leithwood and Riehl, 2003). However, as noted by Hallinger, Bickman and Davis (1996), the primary issue is not whether the principal's influence is direct or indirect; rather it concerns an understanding of the ways in which principals shape effective educational programs by working with teachers, staff, parents and students.

Leadership as an influence process leads to a conceptualization that leadership can be in the hands of many and schools in which teachers were seen to provide influential leadership were also perceived by teachers to be more effective and innovative (Leithwood et al., 1999, p. 121). Rubin defined collaborative leadership as the skillful and mission-oriented management of relevant relationships and the collaborative leader as one who had the ability to convene and sustain relationships (2002, p. 18). Thus, collaborative leaders are viewed as agents of influence. As well, Day, Harris and Hadfield (1999) found that collaborative leaders tend to be emotionally intelligent, persuasive, conscientious and resilient. The importance of shared leadership or distributed leadership models as providing new means for teacher growth has been articulated in recent studies by Planche (2004) and Belchetz (2004). The facilitative role played by those in positions of formal leadership appeared to be a key dimension in the development of more collaborative working cultures. Leaders serve to define those things that are important, providing a clear focus and the framing for that focus. Leaders also provide ongoing support, guidance and encouragement to move initiatives along. Planche concludes that leadership actions appear to have a mediating role, primarily mediating pressures for the staff. This conclusion is confirmed in the study carried out by Belchetz (2004). Evidence from this study indicates that the leadership actions of the participating school principals included the action of 'buffering' or 'filtering' pressures in order to bring coherence and meaning to the focus on student improvement in the school.

Leadership is often the key to productively managing turbulence. Leithwood et. al (1992) describe formal school leadership as a socially constructed role and point out that the expectations of this role have changed dramatically during the turbulence of the reform period experienced over the past decade. Moreover, these authors note," good leadership is exquisitely sensitive to the context in which it is exercised" (p.236). It follows therefore that the nature of the changes that have been experienced in the education field during this time have changed the nature of the work of school leaders. With the implementation of programs considered educationally defensible and the introduction of performance-based approaches that demonstrate improved student achievement, there is a greater focus on building a learning organization in the school that builds capacity from within the school with the purpose of positively impacting improved student outcomes. (Belchetz, 2004).

Leaders of learning organizations and professional learning communities tend to foster a climate of risk-taking and inquiry as well as support relationships that encourage a community of learners. Promoting the right people into leadership positions shapes organizational strategies and climate for years. This is one of the types of decisions where there is the least opportunity for trial and error learning (Senge, 1990, p. 23). Individuals with low needs for uncertainty avoidance, high tolerances for ambiguity, and lusts to experimentation should be recruited as decision-makers and leaders (Hedberg, 1981, p. 21). Schlechty (1990) also believes that strong leaders build cultures that outlive them; they lead even when they are gone. These complex notions of leadership lead us to believe that leaders are critically instrumental in moving systems and schools from first order change to embedding second order change with the promise of sustainability. Thus we examine the literature on first and second order change here.

6. Moving From First to Second Order Change

Some organizational scholars believe that learning is a continuous process and organizations that are in the process of getting better at it depend on the creation of cultures that are supportive [and collaborative] (Senge, 1990, p. 122). The ability of school organizations to collaboratively address the learning needs of faculty, as well as students, can provide the tools for the evolution of schools from isolated, atomistic organizations to responsive, self-appraising learning environments, that are stimulating to both learn and work within (Louis & Kruse, 1994, p. 23). Watkins and Marsick (1992, p. 120) suggest that Argyris' and Schön's error detection model is the best approach for discerning such gaps, and for attacking the root problems which impede organizational learning. Schools, too, must move beyond the simplicity of cause and effect learning, known as single-loop learning (first order change), towards meta- or double-loop learning (second order change) which involves new ways to assemble responses and to connect stimuli to responses (Kelly, 1955, in Hedberg, 1981, p. 8). This meta-learning requires second- order changes, changes in organizational culture and structure (Prestine, 1994, p. 28). First-order changes (ie. changes in core technology) are almost never successfully institutionalized in the absence of complementary second-order changes (Leithwood, 1993, p. 33). Thus, structural and cultural (second-order) changes that are supportive of each other, over a long period of time, provide the opportunities for organizational learning required to successfully introduce first-order change (Sharratt, 1996, p. 26) and the cycle of learning within educational practice becomes continuous.

One opportunity for cultural change involves tearing down obsolete mental models (ie. personal frameworks for understanding mental models) and starting anew. Consistently, individuals and organizations trap themselves in defensive routines that insulate mental models from examination and hence, "skilled incompetence" develops (Senge, 1990, p. 10). Senge defines "skilled incompetence" as teams full of people who are incredibly proficient at keeping themselves from learning (1990, p. 2). In order to curb this, it is important to recognize that structural changes, such as changes in policies and procedures, would not be sufficient (first order changes) without changes in ideas, beliefs, attitudes and "skilled incompetence" (second order changes).

Change involves both problems and attempts to solve problems within school systems. Barott and Raybould conclude that collaboration is a second-order solution to a second-order problem (1998, p.39). Second-order problems exist when the solution itself has become the problem and second-order problems require second-order change strategies. In first order change, change occurs that essentially allows the basic nature of the system to persist. Second-order change is a "change in the rules about how components of a system relate with one another" (1998, p.35).

Further to this description, Elmore (presentation in Toronto, July, 2007) effectively categorized first and second order change as Technical and Cultural change respectively. He defines first order (Technical) change as: schedules, structures, roles, types of professional development, protocols, rubrics, assessments, and accountability systems. Elmore describes second order (Cultural) change as: beliefs about student learning, pedagogical content and knowledge, established norms for group work across groups, discourse about practice through common language, mutual accountability and distributed leadership down into the organization...not traditional supervisory behaviour. Elmore critically acclaims that the work of student improvement is the movement from first order to second order or in Elmore's terms technical to cultural change. We add to that, it's a movement at both the system and school levels and carried out in an aligned and consistent way.

In concluding this literature review, we realize that the problem of changing an organization's culture to embed second order change is more than a matter of surfacing assumptions and encouraging dialogue and collaboration. It also is a matter of unlearning entrenched behaviours and relearning by replacing them with new, relevant responses and mental maps. The ability to reframe perceptions is a powerful way to change behaviours. Often rules and assumptions are so inaccessible in an organization that even leaders fail to identify the patterns and thus are unable to implement new modes of behaviour (Sharratt, 1996, p.24). Learning organizations and professional learning communities are dynamic inside, but must be sensitively plugged into their contexts if they are to have any chance of surviving at all (Fullan, 1993, p. 42). The understanding of organizational culture and its power is integral to the management of change and to organizational learning. Learning has occurred when a teacher has changed practice by acquiring new knowledge, skill, or attitudes (Sharratt, 2001; Leithwood, 1995). The organization has learned when it has developed better systems for error detection and correction; changed the mental models of its members to a new way of doing business; and changed its organizational memory by changing some part of how it encodes memory (information systems, budget, policies, procedures) and captures and encodes knowledge latent in experience (Marsick & Watkins, 1992, p. 119). This is learning as created by second order changes. We address the impact of first and second order change processes by considering the data our system has collected through its Literacy Collaborative reform approach and leadership development model.

3. DELVING MORE DEEPLY INTO THE DATA

As we have stated, although the overall achievement results for students in the YRDSB show significant improvement since literacy has been a focus in the district (Table 1), it is critical that these data are examined in greater depth in order to effect the necessary second order change that leads to sustainability and to less variation among classroom practice. No longer is it sufficient for educational organizations to monitor the progress of the system without having a clear understanding of the complexities underlying the statistics that are intended as accountability measures. To support this process, the large-scale assessment results have been recently analyzed by sub-group populations. In our data analyses to understand where second order change is needed, we have considered 3 areas displayed below: students with special needs, specifically students identified with Learning Disabilities, gender and perceptions of leaders from our recent research.

1. Achievement Results: Students with Special Needs

Upon closer scrutiny of the Grade 6 EQAO assessment results for students with special needs, the improvement scenario shows a different profile than the one shown for all students. The magnitude of improvement in the achievement of students with special needs over the past 5 years does not parallel those of the general population with very small improvements in reading and writing and a decrease in mathematics (Table 2). A similar profile can be seen in the results for students who have been identified with a Learning Disability (Table 3).

Table 2: Achievement Results: Students Identified with Special Needs

| Grade 6 EQAO Assessment | % of Participating Students at Levels 3 & 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2006 | % Increase | |

| Reading | 33% | 35% | 2% |

| Writing | 28% | 30% | 2% |

| Mathematics | 38% | 35% | -3% |

We note that compared to the improvement shown for all students across the district (Table 1), very little or no improvement is seen for students with special needs.

Table 3: Achievement Results: Students Identified with a Learning Disability (LD)

| Grade 6 EQAO Assessment | % of Participating Students at Levels 3 & 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2006 | % Increase | |

| Reading | 32% | 34% | 2% |

| Writing | 24% | 29% | 5% |

| Mathematics | 35% | 33% | -2% |

This very limited improvement is of significant note since the LD population in general is considered to be average or above average intelligence. Thus, not only is there very little improvement, the numbers of student performing at levels 3 and 4, as we would expect of average or above average students, has been and continues to be very low.

2. Achievement Results: The Gender Gap

There is a distinct gender gap in the literacy achievement of males and females according to the EQAO assessment results and this gap has only marginally improved in reading and not improved in writing over time.

Table 4: Achievement of Females and Males - % of Participating Students at Level 3 or 4

| Grade 6 EQAO Assessment | Males | Femails | Grade 6 EQAO Assessment

(% males - % females) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2006 | 2002 | 2006 | 2002 | 2006 | |

| Reading | 63% | 69% | 76% | 80% | -13% | -11% |

| Writing | 59% | 66% | 76% | 83% | -17% | -17% |

| Mathematics | 72% | 75% | 72% | 77% | 0% | -2% |

System improvement is illusionary if districts don't probe further to look more critically at the performance of sub-groups and ask the tough questions that closer scrutiny demands. Taking action is a must and becomes an ethical issue...the moral imperative for our district.

3. Current Research: Perceptions of Leaders

In the 2007 school year, qualitative data was collected regarding the perceptions of leaders on

a number of topics concerning the district's efforts to support staff through transitions and in their development. While still only at the baseline data stage - there is no trend data available at this time - the data do show discrepancies in the perception of the district's current practice regarding a particular issue versus the perception of the priority of the issue. While the perceptions have scored relatively high -(all scores are average scores out of a total of 5) the discrepancy points to a need to adapt current processes to better meet the needs of the principals and vice-principals.

Examples of perceptions that demonstrate this need to move to second order change are reflected in Table 5.

Table 5: Perceptions of Leaders

| Data Collection Indicator | Perceived Current Practice in the board (Response /5) | Perceived Priority in the board (Response /5) |

|---|---|---|

| The board provides support for principals and vice-principals to implement board policies and procedures | 3.85 | 4.42 |

| The board provides human resources to support the principal and vice-principal as instructional leaders | 3.47 | 4.47 |

| The board's placement and transfer process for new principals and vice-principals include supports for success | 3.13 | 4.43 |

| The leadership development framework is consistent with evidence-based best practices, institutionalized and communicated to all | 3.77 | 4.15 |

These data of sub-group performance and perceptions of leaders lead us to make recommendations not only to the research community but also for ourselves as we strive to accomplish second order change that will ensure embedded precision and consistency in classroom practice, long after we are gone. The following carefully thought-out recommendations, in answer to our three research questions, reflect the journey that many of us, as educational leaders, have before us.

4. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DISTRICT AND SCHOOL REFORM

In our context, system leaders define success in terms of the impact on student achievement. Our own experience with large system change has clearly demonstrated for us that reform processes aimed at significant cultural change are not linear or smooth in their evolution. Nor is it easy to ascertain when first order changes that can be shaped by systemic structures and supports are reaping second order benefits in terms of sustaining new cultural norms and behaviours. In answer to our first research question: "What specific elements propel a large system from first order change towards second order changes that sustain improvement processes and student achievement", we feel that there are six elements of systemic change that appear to be propelling us forward towards more sustainable second order progress that we feel are worth noting.

1. System leaders, who provide common key messages, are critical to helping schools focus their reform efforts.

There is a growing interest in the role of the district in supporting principals' efforts in transforming school culture. Hargreaves and Fink (2004) note that 'if we want change to matter, spread and to last, then the systems in which leaders do their work must make sustainability a priority (p.6). The York Region District School Board's journey towards improvement of student achievement has certainly been mobilized through its Literacy Collaborative. This model has involved all schools in our district in similar professional development opportunities. The alignment of system plans with school plans, each being driven by data regarding student achievement, the development of an embedded literacy coaching model, facilitating collaborative work across schools in learning networks and the use of outside "critical friends" are all examples of system leadership decisions meant to focus, motivate, direct and support the improvement efforts of our individual schools. We could site many more examples of intentional systemic implementation strategies. The major point being made, however, is that systemic messaging using common language has been intentional, as consistent as possible and delivered by a variety of system leaders including the director, his management team of superintendents, principals, vice principals, consultants and managers in our system.

We believe our system's mission statement defines our direction. Thus, the first order change processes within this journey such as the assignment of specific staffing to a "literacy teacher role" appear to have been a catalyst towards second order change which now must include deeper forms of dialogue and discussion that 'literacy teachers', as a new form of teacher leadership, are able to have with all colleagues within and across schools. These professionals, in varying degrees, are able to mentor colleagues, model for them and support others in giving them feedback on actual practices within literacy instruction periods during the school day. This role has created another level of colleagueship where teachers appear more willing to accept somewhat formalized help from each other through a pivotal staffing decision.

The challenge is that, systemically, we still have a long way to go in terms of developing an increased critical mass of teachers engaged in altered forms of colleagueship, altered programming decisions based on new learning and the ability to demonstrate a clearer understanding of what is being termed "balanced literacy programming". Not surprisingly, our challenge is similar to that of most school districts. Our collective challenge is finding ways to engage ALL teachers in becoming instructional coaches and mentors for each other. This means continuing to address relationship building amongst stakeholders, continuing to attend to the learning needs of teacher leaders and continuing to address the contractual boundaries which influence how educators interface and work with each other. As well, continuing to build the capacity of all educators involved in the consistent delivery of the instructional program in a site- based, job-embedded fashion remains a significant challenge. Leadership regarding assessment and instructional learning processes is still in the hands of a relative few. Professional development must be reframed to professional learning within working contexts and school culture to reframe 'mental maps' and perceptions regarding professional working norms. It is encouraging that teaching is becoming and must continue to become a learning profession in which classrooms doors are opening to make practice public. System leaders must model being learners themselves. System leadership must continue to wrestle with the complexities of what it means to serve all students and all teachers as learners in reform processes.

2. System supports must be continuous and classroom practice monitored frequently to ensure that ALL students are improving

While the York Region District School Board's leadership enjoys some success in moving overall achievement levels forward, we know that we have just begun the process of sustainable growth and that we continue to have significant groups of students who have not been served adequately. When we scratch below the achievement numbers, we see that there are sub-groups of students for whom focused and intentional work still needs to be done to ensure success for all students becomes a reality, particularly students with special needs and the male student population. More specifically, equity for all students as defined in our Board Plan, will require strategic and consistent implementation of elementary and secondary classroom practice and allocation of resources to close the existing achievement gaps evident in the EQAO assessment results. Continued monitoring of the progress of these students must be a focus of both field superintendents and principals, working together to ensure that the all students have the conditions necessary to be productive and successful citizens in our communities.

To that end, two strategies have been established recently, in YRDSB, and are noteworthy here:

- The "Third Wave" training pilot was developed by Reading Recovery TM Teacher-

Leaders to implement with selected Special Education Resource Teachers (SERTs). The training involved intensive professional development, bi-weekly, in assessment and instruction using identified Grade 2 students (7 year olds) who were not reading. A control group of an equal number was also identified. Field Superintendents had to find principals who were willing to find the time during the school day for their SERTs to be trained as there was no additional staffing allocation created to implement this pilot. Results analyzed at the end of the year are displayed in Table 6 below.

Table 6: Results of First year "Third Wave" Pilot in YRDSB

| Third Wave Students (n=31) | Control Students (n=31) |

|---|---|

| 12 progressed to grade 2 level (reading text level 19-24) | - |

| 11 progressed to entry grade 2 level (reading text level 17-18) | 7 progressed to early grade 2 level |

| 3 progressed to end grade 1 level (reading text level 16) | 3 progressed to reading end of grade 1 level |

| 4 progressed to mid-grade 1 level (reading text level 9-15) | 15 progressed to mid-level grade 1 |

| - | 6 are at K or Sept grade 1 levels |

One SERT (Special Education Resource Teacher) who was in the yearlong Third Wave training comments:

"How rewarding for a little boy who has moved from a level 4 to a level 22 instructional text level (grade level) and is now able to write a story independently. His classroom teacher says she cannot believe the change in him from the beginning of the year until now. He participates in class, he offers to read information to the class, he is much more independent in learning skill areas that challenged him before. He has been identified with a Learning Disability and will receive some support form our Student Support Centre classroom next year. But he will be going into Grade 3 confident, happy and ready to meet new challenges" (June, 2007).

These results have been so encouraging that they cannot be ignored in our student achievement agenda. These improvement data, (which we consider demonstrate second order change by virtue of the changes noted in classroom practice) demand that we must make the hard staffing decisions (first order change) to continue this job-embedded teacher training.

- In November 2006, YRDSB formed the Gender & Achievement Committee to examine the gender and achievement issues within its' schools and to make system recommendations regarding the learning environment and instructional practices to support literacy achievement of males and females. The committee recognizes there is an urgent need to examine the way we teach boys and girls and is there a better way for both that demands differentiated instruction. A compelling story that supports this notion follows:

"Roy (not real name), an identified Special Education student in the Secondary panel came to us from another district. He was a handful. He was suspended numerous times, was defiant, argumentative and uncooperative. Our Junior Alternative Education teacher found that he often acted out when he was given a reading task to complete. He assessed Roy and found that he could not read. One of our English teachers who had been trained in Later Literacy worked with Roy intensively and raised his reading level from grade 1 to grade 7. This took place over a 4-month period. Roy has now passed the OSSLT (Provincial Literacy Test) on his first attempt. As far as his behaviour goes, he is no longer a problem. He was not suspended at all this term. His attitude and self-esteem have all been greatly improved. Roy has now earned 16 credits and has a very good chance of graduating. We at Maple HS are very proud of the efforts that our staff have put forward in supporting Roy" (As reported to Secondary Superintendent, H. Fox, by the Vice-Principal, J. Foti, June 2007).

There are many lessons to be learned from this poignant journey to success for one of our male high school students: collaborative involvement of district and school staff working together to provide support and needed resources; knowledgeable and committed administrators and teachers who go the extra mile; and focused instructional strategies that ameliorate and, in almost every case, supersede behavioural issues in creating enhanced self-esteem and self-efficacy, especially with our neediest students.

3. School leaders must be supported in their growth.

Begley (1999, p.19) has noted that 'in an increasingly pluralistic or global society, administrators must understand and reflect on their motivations, biases and actions as leaders. In the process, they must become aware of the possible existence of relatively fixed core values. This is consistent with the research in the area of emotional intelligence and its influence on supporting improved student learning (Goleman et.al, 2002). The component of emotional intelligence that relates to the principals' beliefs and values has to do with being self-aware. Goleman et. al point out that leaders who are high in emotional self-awareness recognize how their feelings affect their performance in their role. The benefits of principals understanding the impact of their beliefs and values on their decision-making processes in their approach to leadership are thus critical to their success.

Attention must be given to ensuring that aspiring principals have the opportunity to learn the necessary skills. System leadership is challenged in today's context to find, train, and keep young leaders who are motivated to continue the work of reform given its very public pressures and its considerable personal and professional demands. Districts must also consider their long-term plans for leadership succession and shorter-term processes for recruiting and retaining these new principals (Belchetz, 2004). These must be complemented with leadership development supports that enable aspiring leaders to build their innate leadership capabilities. Fullan (2004) has noted that leaders selected for the role of school principal should be able to 'create the conditions under which other leaders will flourish'. He further argues that there 'is no more neglected topic in research policy or practice' (p.4). Supports and opportunities must be available for leaders to lead to greater understanding of how they can bring these conditions about in their schools. We know that if these processes are not effective, schools pay a considerable price. Ineffective leadership can sabotage school reform processes in many different ways.

4. School leadership must be distributed to build systemic capacity in order to ensure full implementation of differentiated instructional practice and thus sustainability.

Distributing leadership processes across the school has become a popular concept in reform literature today. Certainly, distributing leadership responsibilities across the school has been shown to have implications for sustaining improvement student achievement (Harris, 2004). In our own experience, the empowerment of school administrators and teachers is increasingly linked to schools that appear to "be moving" towards improvement. The study carried out by Belchetz (2004) demonstrates that it was through the principal's fostering of professional learning communities in the school focused on improving student achievement that increasing opportunities for teacher leadership involvement and empowerment was evident and welcomed.

A further study of Principals in our district (Fullan and Sharratt, 2006) summed it up in this way:

"We do not see sustainability as linear. There are always ebbs and flows, a time to stand back and regroup and so on. Setbacks are temporary and more likely, in turn, to find ways of reenergizing. Indeed, sustainable organizations do not experience and do not expect continued good fortune but rather stay the course when things are not going well. Persistence and resilience are the hallmarks of teachers and organizations that are self- conscious and confident about their own capacities to win more than they lose and to create their own self-fulfilling prophecies."

That notion leads us to question what does it mean to have an empowered teaching staff in today's context? As Marks and Seashore Louis found (1999), the empowerment of teachers is linked to their participation in school decision-making processes including the development of school planning processes and the allocation of resources.

Some evidence of distributed leadership in our district not only from Principals but also from resource support staff can be found in the following comments from curriculum consultants participating in our most recent internal research study (Backlund and Turner, 2007):

I have noticed an increase in momentum in the second year [of Intensive School Support], confidence is up, the school team is taking on more responsibility/ownership; common language is developing and making conversations more meaningful in the school (Curriculum Consultant, YRDSB.

The relationships that were built last year [in my assigned Intensive Support School] have been strengthened and everyone feels free to take risks. The Literacy Teacher and a few selected teachers on staff have very strong skills and are demonstration classroom teachers. These individuals do not now need my knowledge surrounding literacy or effective instruction. (Curriculum Consultant, YRDSB).

In second order change, distributed leadership, as demonstrated in all of the above quotes, must be evident not only at the district level but also in every school, elementary and secondary. While distributed leadership builds capacity in leaders across the system, we must also ensure that it is cohesive and aligned with the key system messages and leads to full implementation of successful practices in every classroom with every teacher...for every student... without exception.

5. Educators as professional collaborators require specific skills to work together effectively.

The structure that most educators identify as being most in demand is the time that is needed to work together in a collaborative fashion. We also know that unfocused work is ineffective whether collaborative planning time is short or substantial in its supply. As well, the notion of time being given to teachers as a sign of professional respect has been widely accepted while in contrast mandating time to work together has been seen as building resentment and mistrust.

Thus, the challenge for systemic leadership is finding ways to build time for collaborative commitment within contexts that require significant levels of accountability. Supports to the development of collaborative working relationships become very important in terms of moving towards second order change practices. The content of work provides a focus; the form of collaborative work may encompass issues of flexibility and choice. It is the development of trust, however, that is the element of social capital that cements the relationships inherent in the collaborative endeavour. As Mitchell and Sackney suggested, "without trust people divert their energy into self-protection and away from learning" (2000, p. 49).

Pre-service programs as well as new teacher programs, for example, might well set the stage for enhanced professionalism by considering the underpinnings of a trusting school culture as well as exploring how schools cultures become 'stuck' or negative very early in their careers with curricula and development programs. Embedding notions of personal and professional responsibility regarding collaborative skill building throughout the stages of educator development appears to be important. While many skills appear to be assumed and related to basic perceptions of professionalism in education, the lack of certain skills often result in disappointing collaborative efforts and can result in a considerable human and systemic cost. Interpersonal rapport is an obvious advantage when working with others. Specific communication skills are also vital. For example, the ability to facilitate critical conversations was highlighted as an important collaborative capacity (Planche 2004; Planche, 2007). Teacher leaders and administrative leaders who are not able to engage others in compelling and critical conversation are often seen as ineffective.

School districts need critical communicators working together to become engaged in critical thinking and purposeful co-labouring. Reflective conversations that are able to engage collaborators need to be structured with care and guided with skillful facilitation. The integration of strongly developed interpersonal skills as well as skills of effective communication and reflection are a complex order. However, these skills can be enhanced by intentional learning experiences and sufficient practice. It requires the ability to clarify purpose or focus, share ideas and listen critically to the ideas of others, build on the ideas of others, share constructive criticism, to paraphrase understandings, summarize and reflect back the views of others, reframing and refocusing discussions so that constructive actions result. The depth of these skills reminds us that collaborative inquiry is a complex process and to develop a shared sense of purpose regarding collaborative inquiry and practice, leaders need to help others see their place and part in that shared purpose. Building safe arenas for dissent within collaborative processes is also an important facilitation skills that leaders need to undertake. Our collective challenge is to help all educators understand their role as agents of change in school improvement processes and that includes challenging the status quo in order to grow and learn as professionals. The costs that systems have to bear to move from first order change to second order in the area of collaborative work are considerable and may be seen as impediments by those charged with managing always limited time and resources.

6. Systems must define their areas of strength and their areas of deficit to deploy resources differently if warranted.

The analysis of student achievement data provides us as system leaders with a rich source of information but often does not tell a complete story until we scrutinize the available data more carefully. Furthermore, student engagement surveys, staff engagement surveys, parent and community feed back opportunities, focus groups, and a balance of qualitative and quantitative information appears vital in order to gain a more holistic picture of our system's effectiveness. To this end, in the next school year, our District is planning to implement perception surveys for administrators, teachers, students and parents, in order to provide the needed contextual information for school and district planning purposes. To serve students well, we need teachers and administrators working together to become instructional mediators - mediating the mandates of political and system agendas with the immediate and pressing social, emotional and academic needs of students. A first order change process many of our schools have included is reaching out to help build family and community capacity. However, mediation of the needs of the whole child involves second order changes, which embed stronger connections to, and more focus on our students and their families. Inquiry must lead to purposeful action and informed risk-taking to serve students in more beneficial ways. The skills of inquiry require us to become skilled in identifying the social supports necessary to assist our students who are at greater risk of disengagement as well as identifying the educator behaviours that inhibit or facilitate a student's motivation and commitment to self-improvement and self-assessment of learning strengths and needs.

In answer to our second research question: "What does this district need to do to ensure sustainability of students' increased literacy achievement?" we respond that systemic change processes need to involve all stakeholders to move from first order change to embedded second order change which is sustainable. Improvement requires the attention of all stakeholders including students, parents, staff and community partners. Improvement by its very definition demands our ongoing systematic analysis of what we are doing well now and what areas need refinement and change.

We believe that the recommendations in this paper have also addressed the third research question: "do collaborative processes and distributed leadership practice make a positive impact?" Yes, they do. Our issue remains that in order to effect second order change, digging deeper into the sub-group data is critical. This scrutiny must lead to 1) finding ways for every teacher to know when and how to reach every student and 2) having every staff member see her/himself as a leader, instrumental in the dialogue and collaborative action to make student improvement happen. It takes thoughtful action to create change. Everything we dialogue about has little value unless we are able to actualize good intentions into purposeful results.

CONCLUSION

Our own district research (Backlund and Turner, 2007) shows that there are pockets of second order change occurring in some of our schools, as evidenced by the following encouraging comments from our own administrators:

Staff members are growing in their understanding of how all the aspects of literacy are connected and thus changing/adapting/questioning what is occurring in their teaching. (Administrator, YRDSB)

There has been a real shift in culture at [our school] for the positive over the past two years. Teacher willingness to be transparent and vulnerable in their practice is slowly becoming evident over time. We are (at the risk of sounding Fullan-esque) on the cusp of a breakthrough! (Administrator, YRDSB)

We have pockets of people who are changing practice and using data to inform their instruction and others who are not. (Administrator, YRDSB)

Some teachers have made great strides in developing their own personal capacity while others remain unaffected by our actions. Our goal is to broaden its [Intensive Support Program] influence. (Administrator, YRDSB)

However, it is clear to us that further monitoring and supportive work need to be done to ensure that excellence in practice is occurring across the entire system, in every classroom. We can no longer accept variation in practice that leads to variation in student success if we truly believe ALL students can learn. In our context, sustaining improvement and embedding second order change increasingly requires administrators and teachers alike to become consciously skilled classroom leaders and professional collaborators.

REFERENCES

Achinstein, B. (2002). Community, Diversity and Conflict among school teachers. New York: Teachers College Press.

Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for action: a guide to overcoming barriers to organizational change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Backlund, C and Turner, C. (2007). Intensive Support Program Research Report: Administrator and Consultant Surveys. York Region District School Board.

Barrott, J. E. and Raybould, R. (1998). Changing schools into collaborative organizations. In D.G. Pounder (Editor). 1998. Restructuring schools for collaboration: Promises and pitfalls. Albany: State University of New York Press. 24-42.

Begley, P. (1999) (Editor). Values and educational leadership. Albany: State University Press.

Belchetz, D. (2004) Successful leadership practices in an accountable policy context: influence on student achievement. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Bennis, W. and Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders: the strategies for taking charge. New York: Harper and Row.

Bryk, A. and Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in Schools. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cocklin, B. and Davis, K. (1996). 'Creative Schools' as effective learning communities.

Paper presented at the Annual BERA conference, Lancaster University, UK. Retrieved September 4th, 2004, from Education-Line at

http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/000000131.htm

Day, C., Harris, A. and Hadfield, M. (1999). Leading Schools in Times of Change.

Paper presented at the Euopean Conference on Educational Research, Lahti, Finland.

Retrieved on September 4th, 2004 from Education-Line at

http://www.leeds.ac.uk/eduocol/documents/00001241.htm.

Elmore, R. (2007). Presentation in Toronto, July, 2007 for the Ministry of Education, Ontario.

Emihovich, C. and Battaglia, C. (2000). Creating cultures for collective inquiry: new challenges for school leaders. International Journal of Leadership in Education. 3(3), 225-238.

Fullan, M. (1993). Change forces. London: The Falmer Press.

Fullan, M. (1996). Leadership for Change. In The Challenge of School Change. Fullan, M.

(Editor). Arlington Heights: Skylight.

Fullan, M. (2004). Leadership sustainability: System thinkers in Action. Thousand Oaks,

California: Corwin Press.

Fullan and Sharratt (2006). Chapter 5: Sustaining and developing leaders in Sustaining leadership in complex times. B. Davies, Editor. London: Sage Publications.

Goleman, D., Boyatizis, R. and McKee, A. (2002) Primal leadership: Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston, M.A: Harvard Business School Press.

Hallinger, P., Bickman, L. and Davis, K. (1996). School context, principal leadership and student reading achievement. The Elementary School Journal. 96(5).

Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and Trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hargreaves, A. (1995). Renewal in the age of Paradox. Educational Leadership. 52(7), 14-19.

Hargreaves, A. (1996). Contrived Collegiality and the Culture of Teaching in Professional Growth and Development: Delivery and Dilemmas. In Ruohotie, P. and Grimmett, P.P. Editors. Vancouver, B.C: Career Education Centre. 263-289.

Hargreaves, A. and Fink, D. (2004). The seven principles of sustainable leadership. Educational Leadership. April 61(7).

Harris, A. (2001). Building the capacity for school improvement. School Leadership and Management. 21(3), 261-270.

Harris, A. (2004). Distributed leadership in schools: Leading or misleading? ICP Online. Cybertext paper. www.icponline.org/feature_articles/fl4_02.htm

Hedberg, B. (1981). How organizations learn and unlearn. In P.C. Nystrom, & W. H. Starbuck (eds.). Handbook of organizational design, vol. 1: adapting organizations to their environments. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lambert, L. (1998). Building leadership capacity in schools. Alexandria, V.A: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Langer, G., Colton, A. and Goff, L. (2003). Collaborative Analysis of Student Work. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Leiberman, A. (1988). Building a professional culture in schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Leithwood, K., Begley, P.T. and Cousins, J.B. (1992). Developing expert leadership for future schools. Washington, D.C: Falmer Press.

Leithwood, K. (1995). Effective school district leadership: transforming politics into eduction. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Leithwood, K, Begley, P and Cousins, J.B. (1992) Developing expert leadership for future schools. Washington DC. Falmer Press.

Leithwood, K and Riehl, C. (2003) What we know about successful school leadership. (Brief prepared for the Task Force in educational leadership. Division A. American Educational Research Association). Temple University.

Leonard, P.E. and Leonard, L. J. (2001). The collaborative prescription: remedy or reverie? International Journal of Leadership in Education. 4(4), 383-399.

Lipman, P. (1997). Restructuring in context: A case study of teacher participation and the dynamics of ideology, race and power. American Educational Research Journal. 34(l), 3-37.

Little, J. W. (1990). The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers' professional relations. Teachers College Record. 4, 509-535.

Louis, K. and Kruse, S. (1994). Organizational learning in schools: a framework for analysis. New Orleans: Presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association.

Mark, H., and Seashore Louise, K. (1999). Teacher Empowerment and the capacity for organizational learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 35, 707-750.

Mitchell, C. and Sackney, L. (2000). Profound Improvement: Building capacity for a learning community. Liesse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Planche, B. (2004). Probing the Complexities of Collaboration and Collaborative Processes. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Planche, B. (2007). A leadership lens on the complexities of collaboration. Research paper prepared for the Simcoe County Board of Education, Ontario, Canada.

Prestine, N. (1994). Sorting it out: a tentative analysis of essential school change efforts in Illinois. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Sergiovanni, T. J. (2000). The lifeworld of leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Schein, E. (1984). Coming to a new awareness of organizational culture. Sloan Management Review, Winter, 1984.

Schlecty, P. (1990). Schools for the 21st century: leadership imperatives for educational reform. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Scriber, J. P., Hager, D. R., & Warne, T. R. (2002). The paradox of professional community: Tales from two high schools. Educational Administration Quarterly. 38(l), 45-76.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: the art & practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday.

Sharratt, L. (1996). The influence of electronically available information on the stimulation of knowledge use and organizational learning in schools. University of Toronto: Unpublished Thesis.

Sharratt, L. (2001). Making the most of accountability policies: is there a role for the school district? Orbit, Vol.32, No. 1, 33-38.University of Toronto

Sharratt, L. and Fullan, M. (2005). The School district that did the right things right. Annenberg Institute for School Reform. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown University.

Swieringa, J. and Wierdsma, A. (1992). Becoming a learning organization: Beyond the Learning Curve. Wokingham, England: Addison-Wesley.

Watkins, K.E. and Marsick, V.J. (1992). Building the learning organization: a new role for human resource developers. Studies in Continuing Education, Vol. 14, No. 2, 115-129.